What clues are you still missing?

Vance McCullough

“If you want to understand the owl, study the mouse.”

– Apache elder via Rick Clunn

Fifty years. Half a century. I’ve been on this planet that long, all of that living right here in Florida. I’ve been paying attention. But one thing that escaped my notice was the fall shad spawn in the Sunshine State.

Sure, I’ve been aware for decades that our bass spawn at least 6 months out the year. But shad? Never really thought about it. I just thought of the shad spawn as that brief, early morning deal you get on until the sun tops the trees on days when it’s still cool enough in to wear a hoodie at daybreak in say, March or early April.

But a shad spawn in the fall? I never thought to look for it. But because someone shared their experiences with me recently, I am now wiser, if a little insecure about what I still don’t know about the fish in my native home.

My ignorance reminds me of something Rick Clunn has attributed to an Apache elder, “If you want to understand the owl, study the mouse.”

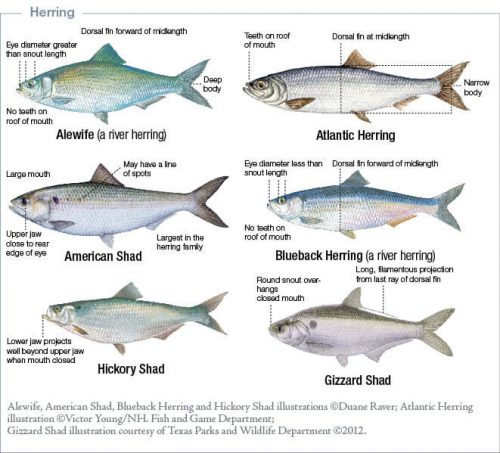

Sage advice considering animals basically eat, sleep and reproduce – kind of like some people I know, but I digress. Forage movements dictate the behaviors of predators, including birds of prey and fish alike. While bass eat a variety of baitfish, it is the shad that is most like the mouse to the bass’ inner owl. But just as there are different subspecies of mice, there are numerous different types of shad across America. Just consider what swims in the Sunshine State alone. From the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission web site:

“Several kinds of shad live in Florida. Gizzard shad and threadfin shad are members of the genus Dorosoma and are statewide, year-round residents of fresh and brackish waters. These are common prey items for predatory fish in many Florida lakes and rivers. American shad, hickory shad, and blueback herring-all members of the genus Alosa-live in the Atlantic Ocean and enter the St. John’s and St. Mary’s rivers in northeast Florida in winter and spring to spawn. Alabama shad and skipjack herring, also members of the genus Alosa, occur in gulf coast rivers; skipjack herring are limited to the panhandle, and Alabama shad occur as far east as the Suwannee River.”

Threadfin and gizzard are well-known to bass anglers and many of our lures are painted to match them, but an often-overlooked cousin is the American shad which, when mature is often bigger than the average bass – record sizes in northern states top 10 pounds. However, as young of the year American shad leave the St Johns River in autumn, they are about 2-to-5-inches long, perfect eating size for a bass population that needs to fatten up for winter and the coming spawn.

A similar phenomenon occurs up and down the East Coast and the around the Gulf of Mexico. The jade depths of the Great Lakes reveal their own baitfish idiosyncrasies, ditto for the moonscaped jewels of our western desert (what is a Kokanee anyway?). But no matter where you fish, the waters always hide some secrets. Keep studying, keep learning. Some things take 50 years to figure out.